Helping families rise above grief

Güncelleme Tarihi:

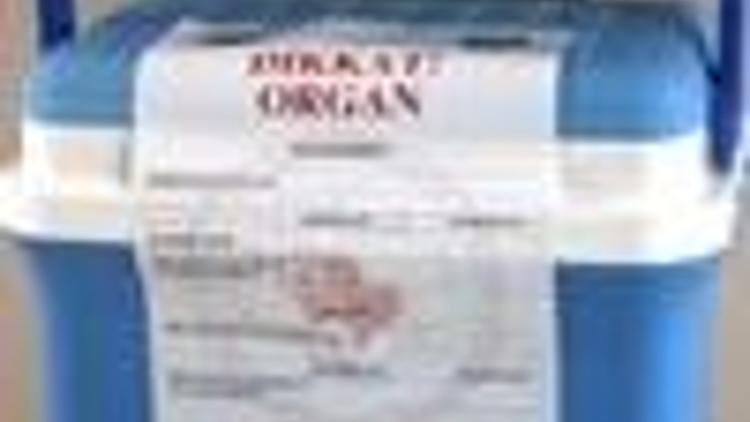

ISTANBUL - They say they would never do this job if they did not know the situation of patients who need organs. The job of an organ transplant coordinator is to convince relatives of deceased persons to donate the organs of their loved ones. While it is hard to demand such a sacrifice from people in their darkest hour, it is also vital, as a successful organ donation is entirely dependent on time. Organs should be harvested and transported in the short period between brain death and heart arrest.

There are 132 organ transplant coordinators in Turkey, 50 of them are on active duty. This year 201 organ donations were made following brain deaths.�

‘I always wear my uniform; otherwise we are mistaken for the organ mafia’

İmren Özbek, 32, is very successful at convincing families to donate the organs of their loved ones. Of the 40 families she met this year she convinced 20 to donate. Working at İzmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital for over a year, Özbek said she is nervous before each meeting, especially if the deceased was young. The hardest thing to explain is brain death, says Özbek. If the relatives are hearing about it for the first time, they ask, “How can he be dead if his heart is still beating?”

Özbek prefers to wear her special uniform to each meeting, “Once, a deceased’s wife had agreed to organ donation and just as she was about to sign the deceased’s brother entered the room in a rage, he tore up the piece of paper and shouted, ‘Do not sign the paper.’ He called me the organ mafia. I had to call security.”

Özbek said some people have the attitude that, given their family member has just died, why should they care about others; while some think the deceased may suffer during the removal of the organs. A lot of them consult imams first, “With four or five cases, the donation did not happen after the family consulted an imam, the answer was no. In one of these cases, I asked for the telephone number of the family's reverend. I called him and asked him whether he would be able to sleep that night knowing four or five patients’ lives could have been saved, but for him.”

‘I will leave if you want me to, but then it will be too late’

Nükhet Çelik, coordinator for the İzmir’s 9 Eylül University Medical Faculty, has convinced families in 10 out of 17 brain death cases to donate organs. Çelik tells the story of meeting a grandmother who recently lost her granddaughter. “Last year, a 16-year-old girl was hurt crossing the street and was brain dead a few days later. The family members said she was raised by her grandmother and so it was only her that could make the decision.” The grandmother was old and unwell, so Çelik had to go to her house to get permission. “I told her why I was there.

I told her that I would leave if she wanted me to, but if I left it would be too late. She agreed to donate her beloved granddaughter’s organs.” Çelik has been an organ transplant coordinator for over 2 years and thinks that because their job occurs right at the time of a person's death and the grief that death has caused, the coordinators become very close to the families involved.

“Accepting death is hard enough and we ask for organs at exactly that moment. I feel what they endure with my heart, sometimes I cry with them. This job would be really hard if I did not know the situation of patients who are in need of organs.”

‘My most difficult interview was with two boys that lost their mother’

Yeliz Gül, 27, said she was barely able to stop herself crying when speaking to two boys, aged 16 and 19, who had just lost their mother.

“Their father was in prison and they had no one else with them. They cried on my shoulder, but said their mother was a very nice person and they wanted to let her give life to others. They agreed to the donation,” she said, adding that the boys were alone and had to handle the funeral arrangements by themselves so she helped them with the process. She even arranged the burial location.

“I cannot forget any of the talks I have had with families, they always leave a mark,” said Gül, who succeeded in convincing six families this year to donate their relative’s organs out of eight cases.

Gül also said misleading stories in the media are very influential on families’ decisions. “For example, a local paper in Antalya printed false news about three kids being found on a mountain with their organs stolen. As a result, some families changed their minds.”

Meeting at gun point

Levent Öztin said they experience strange incidents in the transplant coordination business. “On one occasion it was like standing with a gun in front of me. I explained to a father that if he would not donate, four or five more children from other parts of Turkey might die just like his child. He listened, understood and donated,” Öztin said.

One of the biggest lessons Öztin said he learned was from an imam from the southern city of Isparta. The imam donated the organs of his 13-year-old only son after brain death saying, “Although the creator took him from me so early, this could make his departure a virtue. That is the only reason I can stand my grief.”

Koran as a convincing tool

Süleyman Tilif, an organ transplant coordinator of five years, with 68 donations under his belt from 100 meetings, answers the most frequently asked questions using verses from the Koran. Tilif said the death of children really shocks him and makes his knees tremble. “A 17-year-old boy from Erzurum had hung himself. When brain death occurred, we informed the family.

It was the most crowded meeting of my life. They wanted to consult an imam and asked me whether his organs could end up in the body of a thief or a drunk.” Tilif said the family agreed to organ donation only after an elder told them it was for Allah to decide who receives the organs, not for them.

‘Until 2006, there were no donations from Konya but we changed that’

Melih Azap, an organ transplant coordinator from Konya, said they changed the attitude of the city toward organ donation by visiting factories and prisons, and by talking to people. This year they had eight brain deaths and in five cases, the families donated. Azap said families do not want to give an answer without consulting a religious leader in the community first.

“They ask questions about whether the organ will be given to a Muslim, or who will be seen as a sinner if the receiver of the organ then drinks alcohol. I answer that Allah is all-knowing, he will be able to tell who committed the sin and who had not,” he said.